Simplifying Australian Copyright Law for the Musicians and Music Artists.

What is copyright?

The Oxford University Online Dictionary defines “Copyright” as “the exclusive right given by law for a certain term of years to an author, composer, designer, or assignee, to print, publish, and sell copies of his original work.” (OED. 2020).

In Australia, a critical document in legislation outlines the definitions and provisions of the various forms of copyright and the legalities involved in protecting copyright, The Copyright Act of 1968 (Federal Register of Legislation & Australian Government. 2017). The document itself is over 700 pages long. It is justifiable that there is some confusion and contradiction when applying legislation to music industry publications by reading through it.

This presentation intends to simplify understanding of the legal rights of publications and performers concerning copyright in the music industry. The reader should note that the research conducted for the following is in the context of Australian law in the years 2020 and 2021. Also, note that some conditions outlined may apply to international entities and international laws.

History of International Copyright Legislation & its Application in Australia

Berne Convention

In 1886, a convention or Treaty was created for the Protection of Literary and Artist property by a congregation of members from various European countries. The “Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works” was an agreement between international entities to respect and uphold the copyright.

It states three basic principles;

- Works originating from one contracted country must be given the same rights and protections in each of the other contracted countries.

- Protection and Rights are given automatically and are not conditional upon any compliance (e.g. additional requirements)

- Protections and rights are independent of the existence of the protection in the country of origin unless the protections extended from the country of origin exceeded the minimum requirement of the convention, in which case protections revert to the cessation of the country of origin. (WIPO. 2021)

Following these basic principles, minimum standards were set and enforced as part of the Treaty’s conditions. These standards were revised in the Paris Convention of 1979 to incorporate the evolution and increased access to media.

- the right to translate

- the right to make adaptations and arrangements of the work

- the right to perform in public

- the right to recite

- the right to communicate to the public

- the right to broadcast

- the right to make reproductions (subject to intellectual property and sale of the said property)

- the right to use the work as a basis for an audiovisual work

Australia became a signatory of the Treaty in 1928.

World Trade Organisation

The Berne Convention became the basis for the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement) of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). TRIPS acknowledges and refers to the Berne Convention expanding upon it to incorporate patents, inventions and digital evolution of technology and media. Articles further identify enforcement of the agreement and disciplinary action enacted by the WTO.(Wikipedia. 2021)

Regarding Intellectual Property Rights, the agreement further states;

- Member states must acknowledge end comply with Articles already established in the Bern Convention (1971) and the Paris Convention (1967)

- Whenever the term of protection of a work is calculated on a basis other than the life of a natural person, such term shall be no less than 50 years from the end of the calendar year of authorized publication or, failing such authorized publication, within 50 years from the making of the work.

- The term of the protection available under this Agreement to performers and producers of phonograms (recordings) shall last at least until the end of a period of 50 years computed from the end of the calendar year in which the fixation was made or the performance took place or shall last for at least 20 years from the end of the calendar year in which the broadcast took place.

This agreement became a part of the World Trade Organisation legislation, which is agreed to by all members. Australia signed this document at its original inception and implementation in 1995.

World Intellectual Property Organisation

The World Intellectual Property Organisation is an agency of the United Nations, established in 1967. (WIPO. 2021) There are currently 193 member countries that ratify the WIPO Convention (Copyright Treaty), which is Australia’s case;

- a member of the United Nations

- A member of either the Paris Union or Berne Union. Australia is a member of both, having signed both conventions (WIPO. 1979)

The Treaty was enacted and enforced in 2002; however, it was not signed by Australia until 2006. This was because of issues regarding owners’ rights of trademarked goods and patents. Issues identified by WIPO required the Australian Government to amend Federal legislation government copyright concerning patents and trademarks. This involved the removal of legislation, renegotiation, bill delivery and senate approval by Australian government officials and organizations. This further resulted in two Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Acts of 2003 (Parliament of Australia. 2003) and 2006 (Parliament of Australia. 2006).

After producing and enacting these documents, WIPO granted Australia signatory status to the Copyright Treaty.

(WIPO. 2016)

Australian Copyright

Copyright Act 1968

So we are back to the Act that started it all, The Copyright Act 1968.

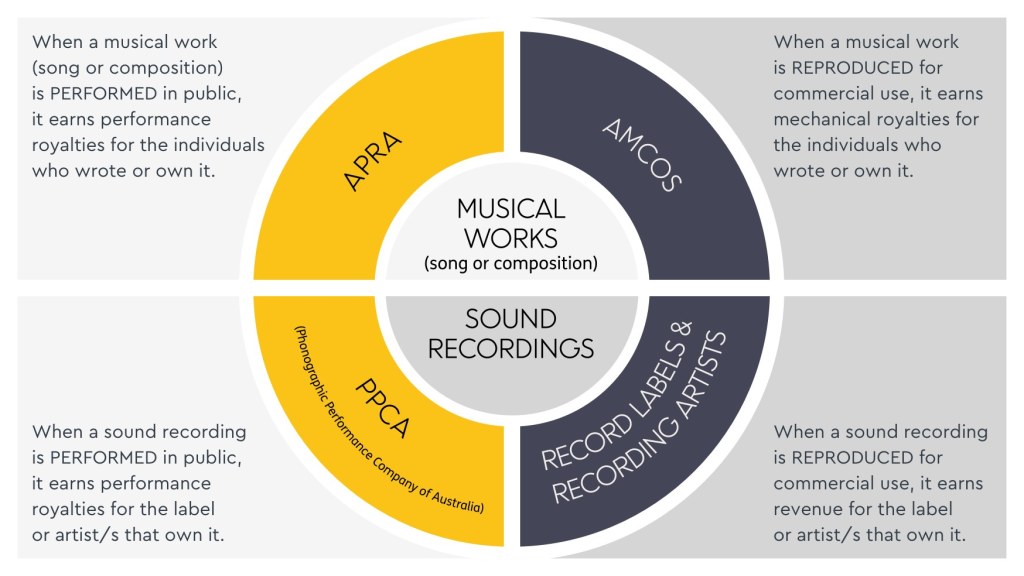

There are three central governing bodies to look after music copyright and licensing in Australia

- APRA (Australian Performing Right Association)

- AMCOS (Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owner’s Society)

- PPCA (Phonographic Performance Company of Australia)

There are also a few organizations that look after the implementation and enforcement of copyright law in Australia

It is sometimes difficult to determine which organization is responsible for which licenses and protections. APRA AMCOS but together a diagram to help musicians and producers simplify the process of working out which licenses are applicable for each circumstance and whom to contact concerning each license form.

APRA AMCOS

The Australian Performing Rights Association (or APRA) was established in 1926 to manage the performing rights of musicians across Australia and New Zealand, assuring that royalties from performances made it to musicians or the owners of the copyrighted work (APRA AMCOS. 2021).

The Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owner’s Society (or AMCOS) was established in 1979 to manage the royalties accumulated through commercial use such as media, streaming, and physical sales (such as Vinyl and CDs). It also covers the reproduction of the work. Both organizations merged in 2019 to form APRA AMCOS after collaborating in providing services to Australian artists since 1997.

Copyright in music can be split into two main strands.

Master Rights is the ownership of the original material or recording. For example, you have composed an original song with lyrics and instrumentation; you have the only copy of the recording and sheet music. Another person cannot legally play it unless you permit them to (Ditto Music. 2020).

This is the central role that APRA occupies regarding music registration and the primary contact point for musicians seeking copyright permissions. Registration also enforces copyright for that piece, granting a serial number or ISRC and permission to use (c) symbol in any future publication (or reproduction) of your work.

Composition Rights is the right to reproduce the ‘Master’ to sell to other parties for commercial use. Mechanical Royalties are the result of this process. These are monies obtained through licensing or the number of ‘plays’ on various platforms (Ditto Music. 2021).

Referring to our previous example of owning the original song, composition rights become essential when publishing your music on an audio streaming platform (such as iTunes or Spotify). You are then entitled to mechanical royalties based on the number of ‘plays’ on each platform. This also includes work on TV and radio, where the copyright owner is paid royalties every time the song is heard. It is likewise the same for selling sheet music online, based on the number of reproductions or sales.

AMCOS is responsible for artists’ compositional rights and distribution of mechanical royalties. Since artists should register their work before publishing, both bodies determined that it would make sense for APRA and AMCOS to combine.

It is free to register with APRA AMCOS, just as it is also free to register your original works. You can access the site below to begin the process.

PPCA

The Phonographic Performance Company of Australia (or PPCA) was established in 1969. They look after licenses and fees for copyrighter holders whose music features in broadcasts, communication and public playing of music (including downloading and streaming) (PPCA. 2021). When work is performed in public, this accrues performance royalties, similar to mechanical royalties.

For Example; A band has been granted permission by the PPCA to perform your song at a series of pub gigs whilst on tour. Every time they play your music publicly, they are required to pay a fee. This fee is then distributed between yourself (as the master copyright owner), the record label (if you are signed to one), and the PPCA (covering legal and administration fees).

It is suggested that when registering with APRA AMCOS, music artists should register with PPCA as well. PPCA has a FAQ section that can assist artists in deciding how they should register (as an artist, creator, or licensor) (PPCA. 2021). More information can be found on the websites below.

As a musician…What Can or Can’t I do?

Copyright can be a landmine field. You are alright as long as you do not step on one. Like most laws in Australia, they are often tied up with additional clauses that we don’t tend to read or acknowledge. This is often the downfall of many music artists. This is not to deter but to instead inform and make aware that a sentence on a page usually has additional meanings. The following are some legal definitions and examples of how music works that can vary from Australian law.

Public Domain

Public domain is defined as “The state or condition of belonging or being generally available to all, especially through not being subject to copyright” (OED. 2021).

Regarding music in its forms, a work can fall into the ‘public domain’ under the following conditions.

For musical works and lyrics, copyright has expired if the creator died before 1 January 1955 and the material was published during his or her lifetime. If not, then the general rule for musical works and lyrics is that copyright lasts for the life of the creator plus 70 years.

For sound recordings, copyright has expired in any recording made before 1 January 1955. If not, then the general rule for sound recordings made after 1955 is protected for 70 years after the year in which it is first published.

(Australian Copyright Council. 2019)

Copyright, after expiry, is not renewable and instantly falls into the category of ‘public domain’.

Most classical works would automatically fall into the public domain and be readily used in new creative works. This is why classical music is often utilised in movies and television as backing tracks on sync. There is little to no licensing contracts and fees to be dealt with.

It is best to check with APRA AMCOS regarding Australian recordings, and publishing studios overseas, before using works falling into the 70 years after the artists’ death, as particular conditions such as legacies and overseas law can affect copyright duration.

FCASE STUDY: Elvis Presley.

- Died in 1977 (does not fall with “creator dying before 1955”)

- His early works were published in the 1940s and 1950s (such as “That’s All Right” (1946)). Copyright law would indicate that such works would technically fall into the public domain for the “70 years after publication date”.

There is a catch; the United States has an additional law stating that works published during this time are entitled to 95 years of copyright protection (even after the artists’ death). In the United States, the likes of “That’s All Right” would not fall into the public domain until 2048. (Cornell University Library. 2021).

For Australia; the acknowledgement of Berne Convention Principle 3

Protections and rights are independent of the existence of the protection in the country of origin unless the protections extended from the country of origin exceeded the minimum requirement of the convention, in which case protections revert to the cessation of the country of origin.

Australia, therefore, must abide by the ruling of the country of origin being the United States, meaning that Australia cannot term Elvis Presley’s works as public domain until 2048.

This case is only one of many where copyright law can be fluid between countries. Therefore, it is essential to determine the ‘public domain’ in each country of origin.

Performance & Publications

Original Music / Works

Any works produced as original by creators are automatically covered by copyright. It is highly suggested that an artist registers their work with APRA AMCOS and PPCA to protect their copyright rights and obtain any fees obtained when using their works, whether by themselves or by other artists.

Covers

Covers are great to showcase talent online, but you cannot profit from these recordings. Be prepared to pay for the privilege to use other artists’ work if you should choose. It is the same for live performances as well as recordings. Permissions can be obtained through Recording Studios or applied through AMCOS or PPCA.

Some online platforms and forums will allow you to publish videos and samples of music on the condition that you do not charge a fee to those who view or listen to the cover version. YouTube has a policy that allows musicians to publish cover content; however, it reserves the right to either block audio or ‘take down the content at the request of the owners of the original piece (Youtube Creators. 2020).

In most circumstances, if the cover music is published for free and acknowledges the original composer/writers of the piece, it puts them in good stead with Youtube. It should be noted; however, YouTube has a strike system in place for copyright infringement. The first strike is a warning; the second strike will result in suspended accounts (and perhaps account deletion).

For example; YouTube and Smule

As a musician, I have dabbled in covers, whether for fun or educational uses (singing lessons, research, practice, etc.). I have used the platform Smule for nearly ten years. Smule is a mini recording studio using backing tracks and recording vocals. Professional artists have used it to connect to fans, often recording duets for fans to participate in.

After recording audio or video, there is an option to publish (or share) on social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Artists should note that the Smule logo and branding are incorporated into the publication by publishing the cover. This is a form of copyright permission, identifying that a cover artist recorded the piece within the platform of Smule.

As mentioned before, YouTube can determine with videos contain copyrighted audio. The user (upload) will receive a nice through email or the ‘YouTube’ Studio, notifying that their video contains copyrighted material; and informs you of the actions required or have already been undertaken in copyright protection of content.

A video example of me singing with Ed Sheeran in ‘Castle on the Hill’ (Smule Inc. 2017). It was used as an ‘April Fools’ joke, as I posted this on my social media platforms. The video incorporates elements that help identify that material and the source from which it came, including subtitles and the ‘Smule’ logo in the bottom right corner. This indicates that I created this video under the terms of copyrighted stipulated by the Smule Copyright and legislative policy, more easily known as the ‘Terms of Use’ (Smule Inc. 2020).

Smule is an internationally utilised platform; however, it operates under the copyright regulation and legislation of the United States.

Sheet Music (Print / Digital)

Sheet music is often a replication or a rearrangement of a sound recording; as such, copyright ownership belongs to the owners and creators of the original piece unless the piece falls into the conditions aforementioned about the age of the piece or whether it is within Creative Commons and public domain.

Online media platforms have ventured into allowing potential arrangers to publish their arrangements online. Permissions for arrangement creation are obtained through these online platforms and publicised to the arranger community. When arrangements are published on that platform, copyright protection is monitored and enforced by that platform’s copyright policy.

It is sometimes allowed that an arranger may obtain a portion (or percentage) of any sales made of the arrangement. This portion is determined by the conditions agreed upon between the original copyright holders and the publishing platform.

The rest is allocated to the services of the publishing platform and the original creators. Essentially platforms practice a fair trade agreement between arranger, creator, publishing house and consumer, thereby enforcing copyright for all parties involved.

SMP Press is an example of a publishing platform. A subsidiary of SheetMusicPlus.com (2021), an online sheet music store, SMP Press allows independent arrangers and composers to publish sheet music under copyright laws of various countries, with the permission of most publishing houses they represent. The availability of arranging copyrighted material is quite extensive because of the extent of their catalogue, from Ed Sheeran to Elvis Presley.

They mention that any copyrighted material must be acknowledged in the publication (usually in a copyright statement). Any sales are also divided by percentage between the arranger and original publishing house (plus a commission for SMP Press).

Concerning the public domain, SMP Press will default to the most prolonged duration of copyright protection (For example, in the Elvis Presley case mentioned in the ‘Public Domain’ section). However, if the publishing house responsible for the work has permitted SMP Press to allow arrangement publication, arrangements can be published and sold on the Sheet Music Plus website, with a portion of the sales going to the original copyright owner.

SMP Press also covers works that are within the copyright laws;

CASE STUDY: Ed Sheeran “Shivers”

First Released: 10th September 2021.

Publishing houses and recordings studios (Atlantic, Sony Music) have allowed arrangements to be made for this work, whether instrumental or choral. The condition is that the published sheet music must have the following information at the bottom of each page (the footer)

Copyright © 2021 Sony Music Publishing (UK) Limited, Sony Music Publishing LLC and Rokstone Music All Rights on behalf of Sony Music Publishing (UK) and Sony Music Publishing LLC Limited Administered by Sony Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219 All Rights on behalf of Rokstone Music Administered by Universal – PolyGram International Publishing, Inc. International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved.

SMP Press’s method (assuming that arrangers stick to the conditions dictated) covers arrangers. It allows for the allocation of royalties to be distributed among the original creators and the arranger under United States copyright law.

Once again, the arranger needs to be aware of the ramifications of publishing in the United States, including the need to register for royalties/ income obtained from the United States (Australian Taxation Office. 2021).

Arrangements (Audio & Visual)

Audio and Visual Arrangement of original work becomes a little more complicated as it becomes a crossover of copyright ownership between the original owners of the original content and the owners of the arrangement or ‘new version” of the piece.

It is difficult and costly for an independent musician to publish a performed arrangement unless other parties are involved or have much money already available for purchasing rights to arrange. Contracting representatives would have distributed any revenue made due to the publication of arrangements to relevant parties on agreed terms.

CASE STUDY: Gordi, Linkin Park, & Triple J

In 2000, Linkin Park released “In The End” as part of their debut album “Hybrid Theory” (Linkin Park. 2000). This piece thrust the band into worldwide popularity. They were able to produce a further six albums before the death of their lead singer, Chester Bennington, in 2017.

There was a public outpouring of grief, particularly in the music industry. Many musicians produced their arrangements of music initially produced by Linkin Park. Australian folktronica singer Sophie Payten, known as Gordi, arranged a mellowed version of “In The End” in honour of Chester Bennington’s passing. This arrangement was performed and recorded on “Triple J’s Like A Version” radio and vlog programme (2017).

Under the copyright agreements made between Gordi and Linkin Park (or their representatives therein), Gordi could broadcast and publish her arrangement on social media platforms but could not publish under her name on further albums. This is an example of how certain conditions can be allowed within certain spheres of publication and broadcasting.

Phonograms (Digital/Streaming)/ Audio Recordings

There are multiple streaming services available for streaming original content. Many stipulate the country in which laws they follow. Services such as Apple Music (Apple, 2021), Spotify (Spotify AB. 2021), and Amazon Music (Amazon, 2021) follow and refer to the ruling of the United States as far as intellectual property. However, if you read through the contract that Artists ‘digitally’ agree to, there is a stipulation regarding International artists and the Berne Convention. Be aware of the distribution company you choose to use, whether it is by a digital platform such as CD Baby (2021) and Distrokid (2021) or ‘bricks-and-mortar’ such as Warner Music (2021).

Distribution agreements may include a stipulation that they would own part of the copyright due to the services rendered to the artists. They would be entitled to a portion of any earnings made by the recording, user conditions stated in the agreements made, or by general copyright law. It is best to consider what services they offer and whether it is worth a share in the copyright of your work.

What if I create music at my University and wish to share or distribute it?

There are a few options available for musical works created in University environments, but it is highly suggested that you seek advice from a Copyright Officer or Librarian. There is a contact list available through the link below. Alternatively, you can contact Copyright Australia for advice.

Universities Australia – Copyright Officers Contacts

Music Copyright in Universities

Educational institutions, including universities, have a special license agreed upon by APRA AMCOS and the PPCA. It is pretty broad in scope allowing for uses that would not usually be allowed under a standard license.

Main points

Playing or performing live or recorded music:

- At university events (including graduation ceremonies) where the ticket price does not exceed $40

- As background music in university spaces and businesses that are 100% owned by the university or an affiliated institution

- By student unions, associations, guilds and clubs that are 100% owned by the university, so long as those activities are permitted within the agreement

- For educational purposes (such as demonstrations, workshops and lectures)

Making audio and video recordings that capture live and recorded music:

- Of university events and graduations

- To live stream university events and performances on the university’s website and official social media channels

- To use for university purposes, including in a course of instruction or for engaging with the university community

- By synchronising music with unrelated visual elements in post-production, ie: incorporating recorded music into another unrelated visual work*

- To be shared on the university’s website or learning management system

Print or Sheet Music

- Reproduce print music, lyrics and tablature in physical or digital formats for use by students and staff for educational purposes or performance at a university event.

- Share digital and physical copies with students and staff

There may be other conditions that the university has that you will need to check. It is best to contact the campus copyright office to get the specifics of the agreement that is in place.

Primary and secondary schools are also bound by similar agreements regarding using and performing music in educational contexts. Once again, if you are working at a school, you should familiarise yourself with the copyright agreement that the school should have in place (APRA AMCOS. 2021).

Original Works

Any original work produced during a student’s study at a university is usually the students’ work, and that student retains such copyright.

CASE STUDY: The University of Southern Queensland Query

As part of the research for this presentation, I sent an email to the University of Southern Queensland Legal Office outlining the scenario of creating original work in the university setting and who is entitled to the copyright therein. I received a reply from the Legal office outlining the current policy of Original Works produced at USQ.

Email to USQ Legal Office:

I am seeking information regarding copyright of music in audio, digital and print. I am creating a document as part of my Bachelor of Creative Arts Project to help Music Artists understand copyright and how it applies to them (what are their right, etc).

I wanted to ask when sharing work, who actually is the copyright owner? I can give an example.

I created an original song, using no additional sources (sampling, copying). I use this as part of an assessment item at USQ. Do I still retain copyright ownership being the creator? Or does the university own it because of academic copyright?

I am a published music artist, but would like to be able to release my content after graduation (audio and sheet music). I have already set up an agreement through third party (SMP Press) to publish my sheet music. Audio I would release as an independent artists through music streaming platforms and YouTube.

(Talbot. S. 2021. Copyright for Music publication [Email])

Reply:

As per the USQ Intellectual Property Policy (https://policy.usq.edu.au/documents/13345PL#5.8 ) the University makes no automatic claim to ownership of Intellectual Property created independently by Students who are not Employees of the University.

If you are not employed by the University to create this work, you retain the copyright to this original work.

Copyright Law regarding musical works often relates to separate items of copyright that are combined to form the whole work. For example, the sheet music, sound, lyrics, etc. With regard to your example, you have advised that you have entered into an agreement with a third party (SMP Press) for the sheet music and thus you would need to look at that agreement to see whether you have retained your copyrights or whether you have signed these over in whole or in part.

If you were to enter into any agreements with other platforms to publish your work e.g. streaming services or YouTube, you would again need to look at the licensing agreements or contracts associated with these platforms. This would also be the case for hard copy publishing of your work.

(McKindley, E. 2021. Copyright for Music publication [Email])

Creative Commons

Creative Commons is an international organisation that operates as an entity that allows for some aspects of copyright to be waived.

Every time a work is created, it is automatically protected by copyright. In Creative Commons (or CC), creators can distribute content for free and allow others to use the content for their creative projects.

Many familiar platforms that operate under the Creative Commons license. You would be familiar with;

- YouTube

- SoundCloud

- BandCamp

- MusicBrainz

- Vimeo

There are many others that you can locate through searches.

There are six forms of CC licenses, each with different combinations of elements for use. The four elements are;

- Attribution (BY) – You must credit the creator, the title and the license that the work is under.

- Non-commercial (NC) – Van be used for file sharing, educational use and festivals; however cannot be used for advertising and for-profit purposes. Basically, you cannot make money from the content.

- No Derivative Works (ND)- You cannot change the original work (cropping, editing or using music in a film). Remixing is not allowed. You need to seek additional permission if you wish to do any of these activities to work shared.

- Share Alike (SA) – Any new work produced using materials must be made available under the same terms of the license.

(What are the Creative Commons licences? 2009)

A flow chart illustrated below can be used to decide which license is appropriate for the conditions you wish to impose on the content you share.

There are several factsheets that provide elaborate descriptions available on the Creative Commons Australia or Creative Commons International websites. A license tool also allows you to answer a few questions about what you intend to do with the content;it generates a code that can then be added to your content or added to websites. Once these license have been made public with your content, your content is covered by the (CC) license conditions that you have stipulated.

Although Creative Commons cannot be used for monetary value, many artists have used Creative Commons to promote their works. Even though access is free to everyone, the resulting publicity has allowed many to build a following.

CASE STUDY: Nine Inch Nails (NIN) – The Slip

In 2008, the band released their seventh album, “The Slip”, online under Creative Commons, allowing for mass distribution in a short amount of time. Publicity was sparked when it was discovered that the music was available for free under the Creative Commons license chosen, as long as it was not shared or illegally downloaded. Any remixes made from the content also feel under the same conditions, so creators could not make money from NIN content.

The worldwide publicity that the band garnered from this manoeuvre allowed them to promote their upcoming international tour of ‘The Slip’ and their previous album ‘Ghosts I-IV’ (also under Creative Commons license).(Creative Commons.Org. 2012)

To highlight the reputation of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, after the release of the album, they were both asked to contribute music both as a band and original compositions to the film “Social Network” (2011). Their contribution was further acknowledged worldwide, winning Golden Globes and Academy Awards for Best Composition.

Bibliography

- Amazon. (2021). Amazon Music: Free Streaming Music. Amazon Music. https://www.amazon.com/music/free/?_encoding=UTF8&ref_=sv_dmusic_3

- Apple. (2021). Apple Music. https://www.apple.com/apple-music/

- APRA AMCOS & PPCA. (2021, April 1). Universities Music Licence. APRA AMCOS. https://www.apraamcos.com.au/music-licences/select-a-licence/educational-institutions/licensing-for-universities

- APRA AMCOS. (2021a). APRA AMCOS logo [Image]. https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=i&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwordsbynuance.com.au%2Fportfolio%2Frock-n-roll%2F&psig=AOvVaw3862U2cExZcVhtJjAUkPPH&ust=1635320915951000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAgQjRxqFwoTCOCzjKjL5_MCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAP

- APRA AMCOS. (2016, April 26). What is APRA AMCOS? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9iZsW-U1QQ&feature=youtu.be

- APRA AMCOS. (2021, September 3). APRA AMCOS | About Us, Music Licensing & Royalties. https://www.apraamcos.com.au/about

- APRA AMCOS. (2021a, August 6). Music Licensing For Schools. https://www.apraamcos.com.au/music-licences/select-a-licence/educational-institutions/licensing-for-schools

- Australian Copyright Council. (2019, November). Music & Copyright INFORMATION SHEET G012v16 [Fact sheet]. https://www.copyright.org.au/browse/book/ACC-Music-&-Copyright-INFO012

- Australian Taxation Office. (2021, June 24). Foreign and worldwide income. https://www.ato.gov.au/Individuals/Income-and-deductions/Income-you-must-declare/Foreign-and-worldwide-income/

- CD Baby. (2021). CD Baby – Digital Music Distribution. CD Baby. https://cdbaby.com

- Cornell University Library. (2021, March 17). Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States | Copyright Information Center. Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States. https://copyright.cornell.edu/publicdomain

- Creative Commons Australia. (2009, June 18). Which Creative Commons license is right for me? [Poster]. https://creativecommons.org.au/content/licensing-flowchart.pdf

- Creative Commons Australia. (2009, June 19). What are the Creative Commons licences? [Poster]. https://creativecommons.org.au/materials/factsheets/cc-licences.pdf

- Creative Commons Australia. (2015, October 9). Fact sheets | Creative Commons Australia. Creative Commons Australia | Creative Commons Works to Increase Sharing, Collaboration and Innovation Worldwide. https://creativecommons.org.au/learn/fact-sheets/

- Creative Commons.Org. (2012, July 12). Case Studies/Nine Inch Nails The Slip – Creative Commons. Creative Commons Wiki. https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Case_Studies/Nine_Inch_Nails_The_Slip

- Distrokid. (2021). Easiest way for musicians to get into Spotify, Apple Music & more. https://distrokid.com

- Ditto Music. (2021, May 11). What Are Mechanical Royalties? Explained for Musicians. Ditto Music Unsigned Advice. https://dittomusic.com/en/blog/what-are-mechanical-royalties-explained-for-musicians/

- Federal Registor of Legislation & Australian Government. (2017, June 30). Copyright Act 1968. Federal Registor of Legislation. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2017C00180

- Linkin Park. (2000). In The End, on Hybrid Theory [Music Recording]. Warner Brothers Music. Los Angeles, United States.

- Linkin Park. (2009, October 26). In The End [Official HD Music Video] – Linkin Park [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVTXPUF4Oz4&feature=youtu.be

- McKinley, E. (2021, October 10). Copyright for Music publication [Email]

- Oxford University Press. (2020, December). copyright, n. (and adj.). OED Online. https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/view/Entry/41314?result=1&rskey=OhAJWm&

- Oxford University Press. (2021, September). public domain, n. OED Online. https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/view/Entry/265942?redirectedFrom=Public+Domain&

- Parliament of Australia. (2003, June 26). Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 2003. Federal Register of Legislation – Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 2003. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2004A01132

- Parliament of Australia. (2006, September 28). Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 2006. Federal Register of Legislation – Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 2006. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2006A00106

- PPCA. (2021, August 3). PPCA – An Intro For Indies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4dpT5m6SBY&feature=youtu.be

- PPCA. (2021a). Artists | PPCA. Artists FAQs. https://www.ppca.com.au/artists/faqs

- PPCA. (2021a). What we do | PPCA. What We Do PPCA. https://www.ppca.com.au/about-us/what-we-do

- Sheet Music Plus. (2021). SMP Press – Sheet Music Plus. SMP Press. https://smppress.sheetmusicplus.com

- Smule Inc. (2017, March 3). Castle on the Hill. Smule. Retrieved October 13, 2021, from https://www.smule.com/recording/ed-sheeran-castle-on-the-hill/998033126_1073005507

- Smule Inc. (2020, October 1). Copyright and Intellectual Property Infringement | Smule Social singing karaoke app. Smule Social Singing Karaoke App. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from https://www.smule.com/en/copyright

- Spotify AB. (2021). Listening is everything. Spotify – About Us. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.spotify.com/us/about-us/contact/

- Talbot, S. (2021, September 27). Copyright for Music publication [Email]

- The Phonographic Performance Company of Australia. (2021). PPCA logo [Image]. https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ppca.com.au%2F&psig=AOvVaw2eJcBNcMYG6nlyMRiSQ9CK&ust=1635321214136000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAgQjRxqFwoTCJidm7PM5_MCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

- The World Intellectual Property Organisation. (2021). Summary of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886). WIPO. https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/summary_berne.html#_ftnref2

- Triple J [Triple J “Like a Version”]. (2017, October 5). Gordi covers Linkin Park “In The End” for Like A Version [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPQ7y6ZYPto&feature=youtu.be

- Warner Music Incorporated. (2021). Home / Warner Music Home. Warner Music Homepage. https://warnermusic.com.au

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2017, February 7). What is Creative Commons? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPZTh2NKTm4&feature=youtu.be

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021, September 19). TRIPS Agreement. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRIPS_Agreement#cite_note-8

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021a, June 27). APRA AMCOS. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/APRA_AMCOS

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021b, September 17). Trent Reznor. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trent_Reznor#Awards

- World Intellectual Property Organisation. (1979, September 28). Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization (as amended on September 28, 1979) (Authentic text). WIPO IP Portal. https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/text/283854

- World Intellectual Property Organization – WIPO [World Intellectual Property Organization]. (2016, October 26). What is WIPO? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYZxqJCno44&feature=youtu.be

- World Intellectual Property Organisation. (2010, April 27). WIPO logo [Image]. https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fipkitten.blogspot.com%2F2010%2F04%2Fthat-new-wipo-logo.html&psig=AOvVaw2-0gt7a8Vn1fNMeWl04Qhp&ust=1635320661795000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAgQjRxqFwoTCIiJiKvK5_MCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

- World Intellectual Property Organsation. (2021). Inside WIPO. Inside WIPO. https://www.wipo.int/about-wipo/en/

- World Trade Organisation. (2021). WTO | intellectual property (TRIPS) – agreement text – general provisions. Part I — General Provisions and Basic Principles. https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_03_e.htm

- World Trade Organisation. (2016, July 19). WTO Logo [Image]. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fworldtradeorganization%2F&psig=AOvVaw1rciuTQEHHADCC0BMwmKpc&ust=1635320268551000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCLDR3_XI5_MCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAJ

- Youtube Creators. (2020, May 19). Copyright in YouTube Studio: Addressing Copyright Claims with New Tools, Filters and More [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bv4CvzyAkV0&feature=youtu.be

Music Copyright in Australia © 2021 by Sarah Talbot is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Music Copyright in Australia © 2021 by Sarah Talbot is licensed under Attribution 4.0 International. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/Music Copyright in Australia © 2021 by Sarah Talbot is licensed under Attribution 4.0 International

About the Author

This document was created by Sarah Talbot, a Creative Arts (Music) student at The University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia.

The research was conducted and published as part of the final project-based assessment for the Bachelor of Creative Arts degree (2021). The outcome of this project (being this document) was published under Creative Commons License with the permission of the University of Southern Queensland.

Leave a comment